Bartholomew Duhart’s work always attracted attention.

He was just a builder, a general contractor. But he never was satisfied with the conventional. Whenever he could, he thought up unusual touches that set his work apart.

If you’ve ever driven down Pio Nono Avenue, near the Frank Johnson Recreation Center, you’ve seen one of his creations. Off the side of the road, in the 1600 block, sits a cemetery beside what is now the Jesus Mission of Love Holiness Church. You can’t miss the big arches at the entrance.

The cemetery arches on Pio Nono Avenue. (Photo by Oby Brown)

Duhart designed and built them, a tribute to his mother and father, who are buried there.

In fact, the arc of much of his life’s work stretches across the adjacent Unionville neighborhood. That’s where you’ll find much of his genius.

At least what’s still standing.

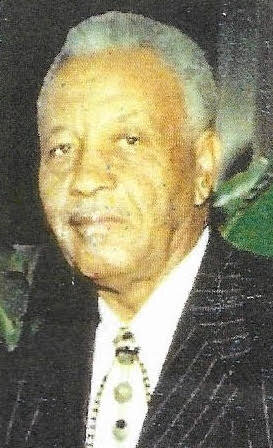

Cecilia Duhart Taylor and her husband, James. (Photo by Oby Brown)

Some artists have to sketch or paint. Others work in clay. Duhart was a gifted builder, driven to create in a way you’d never seen. He was fascinated with curves and circular shapes.

“He would always think out of the box,” said Cecilia Duhart Taylor, the oldest of his three daughters. “He loved doing unusual buildings and brickwork. He wanted to catch your eye and make you wonder what it was.

Photo by Wini McQueen, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Sciences.

“He didn’t think of run-of-the-mill work. … A lot of people would ask him to build for them because they knew it was going to be unusual.

“It was truly his gift. … He was one of a kind.”

Duhart’s studies at Ballard-Hudson Senior High School, including masonry classes, helped stake the course of his career. Later, he took building-related classes at night — mechanical drawing, blueprint reading — through the Masonry Union to enhance his skills.

Bartholomew Duhart

Duhart — friends called him “Bart” or “Sugar” — married the love of his life, Clara, when she was 19. Clara lives in the Atlanta area now with one of her daughters.

In a 1978 interview with fabric artist Wini McQueen, Duhart discussed one of his most memorable projects: a multilevel, 1,200-square-foot restaurant on the site of what was then called the Unionville Recreation Center. It had six circular windows, each of them 8 feet in diameter.

He explained it this way to McQueen: “Circular windows seemed special to me. I’d never seen another building with six (such) windows.”

Photo by Wini McQueen, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Sciences.

“He was always putting something circular in almost everything he built,” Taylor said.

It stood for just 18 months, though, before Duhart sold the property to the city of Macon to build the rec center.

Two other projects still stand nearby, although they’ve seen better days.

They’re both off Columbus Road, just before its intersection with Mercer University Drive.

Duhart built one of them in the late ’80s, said James Taylor, Cecilia’s husband. An old photo that McQueen took shows him in front of the building with the sign In Spirit Saving Bank in the background. Its last use was a Chicken Wings & More restaurant. There are arches on top and whimsical touches all around the site now, including a stone rooster atop semicircular layers of red brick.

Behind it stands what must have been the talk of the neighborhood at the time: a prayer tower. It looks like a space-age treehouse. It sits on a huge metal pedestal. The prayer room itself is about 12 feet across and more than 8 feet off the ground. Many of its windows are shattered, though, and some of the copper shingles are long gone.

He “got sidetracked” on the tower and never finished it, James Taylor said. “He had a lot more work than he could ever do. He always wanted to do it all himself.”

But he made time for fun too.

Years ago, there used to be a Black heritage festival in and around Washington Park each spring. It included a parade. Taylor remembers her father building a miniature replica of a church — big enough for her and other children to stand inside — so they could wave out the windows to spectators along the parade route.

Duhart built homes — some for his five brothers and two sisters — and churches too (Two of them are on Log Cabin Road.) He and his brother James once ran Duhart Brothers & Builders.

Photo by Wini McQueen, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Sciences.

Another brother, Harold, “the one who is a professional architect, says about my work: “It certainly cannot be put on paper,” Duhart said during McQueen’s interview. “And in fact much of what I do is too complicated to draw. ... He often says I am the one who should have been the architect.”

He once had the “wild idea” of becoming a professor. “But I simply told myself that if by any chance that plan failed, I’d settle for nothing less than being a professional.”

His projects were always on his mind. “I put an unlimited amount of planning into these structures,” he said. “How much? At night, in the morning, during my working hours. I kept my mind on these things.”

Said Taylor, “He knew it like breathing. He could think up something in his mind and draw it out.”

‘WE WERE INVISIBLE’

McQueen was one of the first people to take note of Duhart.

In the late ’70s, she set out to incorporate different aspects of Black life “into the history of white Macon.” She wanted to “find and document Black people as the builders of this material world that we live in in Macon.”

“We were invisible,” she said.

“I began my search without knowing a lot of people at all.” She was looking in particular for artists and workers in skilled trades.

Her daily travels often took her down Montpelier Avenue. Each time there she saw “a gigantic, arching sculpture, maybe 20 feet high” made of “slanted legs of brick” in front of a simple white house.

“That was the structure that attracted me to Duhart’s work,” she said. (It’s no longer standing.)

Notes from McQueen’s 1978 interview with Duhart.

Soon she had reached out to Duhart and scheduled an interview with him.

“He was such a self-contained, self-made person,” she said. “Very quiet, soft-spoken. He seemed to be very spiritual.”

His projects, she said, “attracted me because they were so African-like — round windows, … doors that were different.”

A collage of Duhart’s work was part of McQueen’s 1999 exhibit at the Museum of Arts and Sciences titled “Make Do: African American Crafts in Central Georgia.”

She worries that his story and his legacy, like that of so many other talented Black achievers, will be lost to time.

“You can’t find anything visual about him,” she said. “In the Black community, you don’t have … the leisure to create these records. So these stories, especially of Black Americans’ histories, get erased. It’s destruction of our history. Duhart is a perfect example.”

Photo by Wini McQueen, courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Sciences.

She added, “He was a visionary. If society had been more open to him, we would have had more to celebrate. … I want his memory to stay with us.”

Cecilia Taylor feels the same way.

She is proud of her dad. And it’s not just because of the things he built. His father was a minister, and Duhart, in 1980, answered the call to the ministry himself.

He died in 2006. He would have been 85 years old this year. Family members had been planning a 50th-anniversary wedding celebration for him and Clara right before he died.

All during his life, he looked for ways to give second chances to folks who needed a break, even if they’d just gotten out of prison.

“He tried to get them on the right track,” Taylor said. “He would make you feel like you had dignity. He really wanted to help our people, the downtrodden, the thrown away. He had a compassionate heart.”

She still runs into people today whose stories about her dad begin this way:

“Your father helped me become a brick mason.”

“I had no tools, and he gave me my start by loaning me some.”

She remembers the stories they told about him at his funeral, which lasted more than 3 ½ hours.

“They were mind-boggling. Just to hear all those things he had done. … I had no idea.

“Every big pastor in Macon was there,” she said. “All of ’em knew Daddy. I was so proud.”

Many days, when she’s out and about near one of his old work sites, Taylor thinks of her dad and feels a tug to stop, which she does sometimes.

“You can’t imagine that one person could build the way he did,” she said. “Now, I just want to touch the brick he touched.”