Social distancing — and disruption. The closing of schools, factories, small businesses and churches. Quarantines. Panic buying.

They’re all making the news these days, harkening back to the so-called “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918.

An estimated 30,000 Georgians died from it. All told, about 675,000 Americans succumbed, most of them young adults 20 to 40 years old. Worldwide death estimates range from 50 million to 100 million — many of them soldiers, in trenches and barracks.

An emergency hospital in Kansas during the 1918 influenza epidemic. (National Museum of Health and Medicine)

Back then there were no vaccines, antibiotics, ventilators or electron microscopes. Health officials could not test people with mild symptoms so they could self-quarantine. There was little protective equipment for health-care workers. And it was almost impossible to trace contacts, since this particular strain of H1N1 flu seemed to engulf entire communities so quickly.

The outbreak came in waves. The first one hit that spring. The second, in the fall, was the most deadly. (Health officials are worried about that prospect now in the face of our current circumstances.)

In all, a half-billion people were infected — about a third of the world’s population at the time. One estimate says the virus infected up to a quarter of the American population of about 103 million people.

Safety guidelines from Illustrated Current News (National Library of Medicine)

It was a silent foe for months. In the early days, many folks didn’t take it seriously. Back then, authorities “didn’t know what was happening, didn’t know what to do and, therefore, they did the human thing, which is to say it’s not happening,” Dr. Alfred Crosby says in his book “America’s Forgotten Pandemic.” Then people started dying.

In Georgia, the flu wave hit Camp Hancock near Augusta in early October. Recruits received physicals, then were sent off to crowded training camps for later deployment to Europe to fight in World War I. Military trains brought the virus to camps near Atlanta, Columbus and Macon — Camp Wheeler — before it spread to nearby cities. (And Camp Wheeler had just dealt with a measles epidemic the year before.)

Downtown Macon in the early 1900s.

“Today in Georgia History” pegs the date the virus descended on Macon as Oct. 15, 1918. “The Spanish influenza epidemic sweeping the nation hit Macon, with 250 new cases reported in the previous 48 hours.”

Two huge forces were at cross-purposes that fall: continued soldier recruitment to fight (and the close quarters that effort entailed, from military trains to troopships), and the need for social distancing and shutting down activity to quell the virus’ spread.

It’s hard to believe, but the virus and its devastation weren’t often front-page news at the time, at least not in Macon.

The major countries fighting in the war didn’t want to give their enemies any advantage, so the extent of the flu’s rampage — from both local and national leaders — was often minimized. There was wartime morale to consider. And officials wanted to preserve the public order and avoid panic.

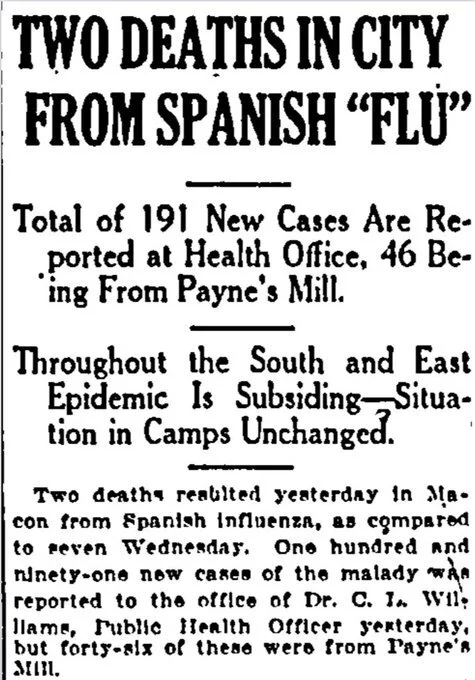

Dispatches about the flu often ran on page 3 inside The Macon Daily Telegraph, said Joe Kovac Jr., a senior reporter for The Telegraph who looked at the paper’s coverage and tweeted about the outbreak recently:

“Our Spanish Flu coverage in Macon in October 1918 included an editorial on embracing inconveniences to avoid spread. (Wearing masks appears to have been encouraged: “A city of bandaged faces is better than coffins piled up in our morgues.”)

One subhead read: “Total of 191 New Cases Are Reported at Health Office, 46 Being from Payne’s Mill

Spanish flu update in The Macon Daily Telegraph.

From an editorial of the day titled “Flail the Flu,” which Kovac cited:

“If these men who have our community health in charge come to the decision all public gatherings should be closed they will act promptly and without fear because public sentiment is already strongly for that,” it read in part. “Fortunately it seems we are so far from the epidemic stage in Macon there is every hope it will not even threaten to reach that stage and that as it stands now it can be as well handled by people going pretty well as usual about their affairs provided they exercise due personal diligence in protecting both themselves and other people.”

As for our current challenge, we don’t know yet if the past is prologue, as Shakespeare told us. But we do know this: In this time of great uncertainty, what has gotten us through other national crises will serve us well now: Setting aside differences and pulling together. Helping each other however we can, from a video call to a grocery run for an older neighbor. Staying connected, through social media or across a backyard fence. Letting others know that they are not alone.

Stay safe and take care. And let us hear from you.