Flint’s Grocery is gone. So too are Weber’s Cafe, Jay’s Beauty Salon and the Rathman/Lewis drugstore, “where you get what the doctor ordered.”

The Middletown Journal, like hundreds of its latter-day brethren, has also shut down.

They were all part of the filming for “Hillbilly Elegy” along Poplar Street. Now, workers have knocked down scaffolding and repainted storefronts up and down the street.

Photo: Oby Brown

It was our latest close-up for a major film, and several members of the small army of women and men working here said Macon should be proud of what it has downtown.

In particular, what it has saved downtown.

“You’ve got great buildings,” said Rick Riggs, the charge scenic artist on the set. “We were very pleasantly surprised at the architecture around town. … You’ve got great little storefronts. … There’s a great opportunity to revitalize the downtown area. We see it.”

Photo: Oby Brown

Riggs was standing outside a row of remade storefronts in the 600 block of Poplar. He described the process of replicating street scenes from Middletown, Ohio, where most of J.D. Vance’s bestseller is set, during three periods: the late 1990s, in 2012 and the late 1940s -- in that order -- for shooting. Workers had to “distress” a site one day, then use historically accurate touches -- appropriate colors, for example -- when they re-created the boom times of post-World War II Middletown.

In all, at least 20 stores or buildings were transformed for filming across the county, most of them in and around downtown. Ron Howard is directing the Netflix movie, which stars Amy Adams and Glenn Close. The memoir tells the story of Vance’s family in Middletown and their struggles with poverty, alcoholism and abuse.

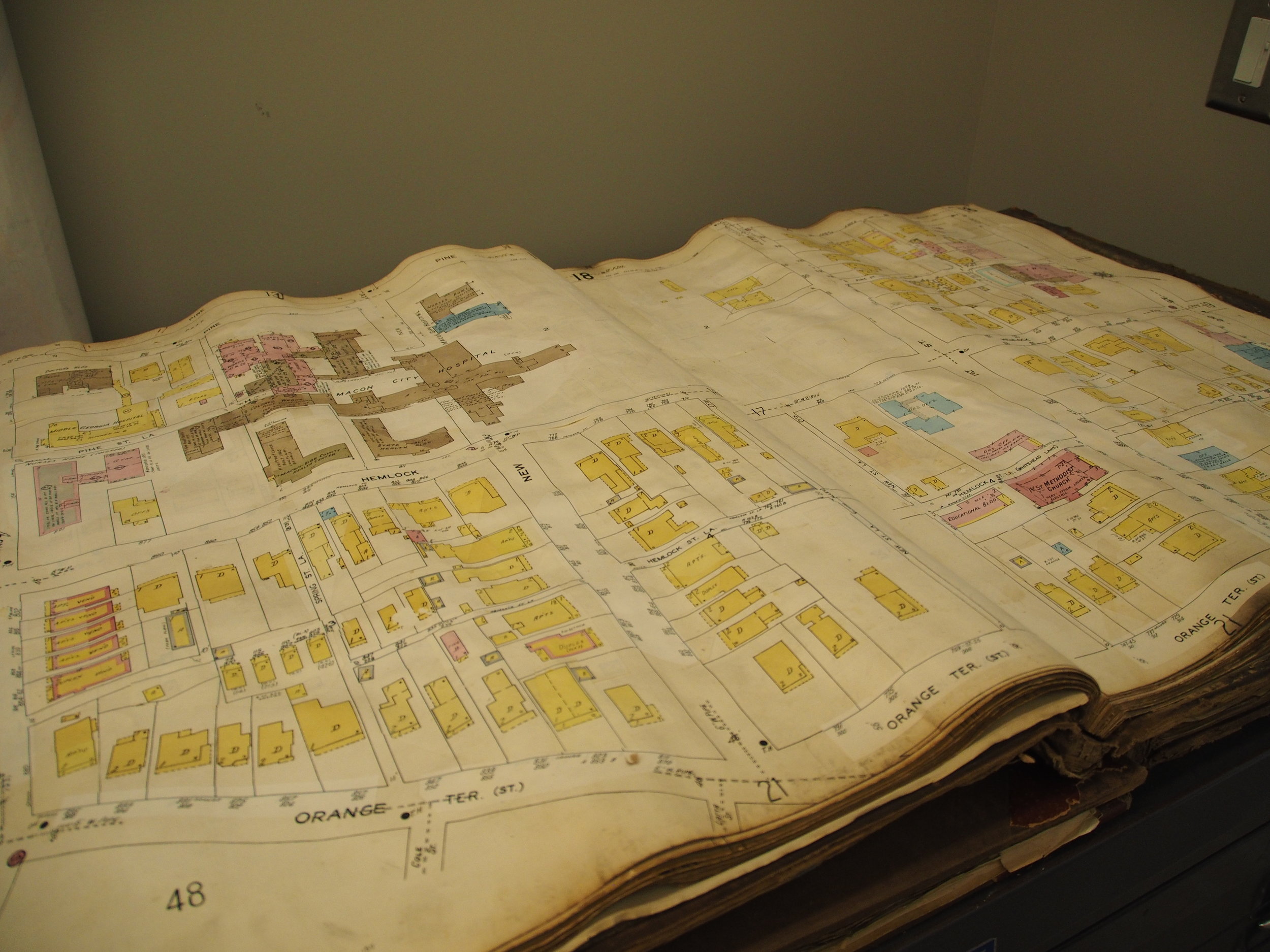

During the height of filming in Macon, one worker took a break and extolled what he’d seen downtown. Standing on the sidewalk, he noted the old Armory Building at the corner of First and Poplar, which was completed in 1885, then pointed out St. Joseph Catholic Church a little farther up the hill.

He called downtown Macon “a gold mine.” The buildings, by and large, are in good shape, and for movie purposes, you can take a store, add neon signs and you’re back in the 1950s. Then you can take out the neon and add LED lighting for a more modern look. But the sites work equally well for both settings, he said.

Photo: Oby Brown

Most of the folks in town for filming had never been to Macon, and almost all of them are gone now. Matt Sparks, a native of Jefferson, near Athens, is getting to know the city well, though.

He was assistant location manager for “Hillbilly Elegy” and a scout too. He arrived in town about a month before shooting began, and he’d just been in Macon in April for four days of shooting on HBO’s “Watchmen” series. During that filming, workers turned parts of Second and Cherry streets into 1940s Brooklyn.

“There’s a lot of room for opportunity here,” he said. “I look at the buildings and wonder, ‘What did this used to be?” Downtown Macon, he said, “has so much to offer.”

Plenty of forward-thinking Macon residents have reached the same conclusion in recent years as they converted long-dormant buildings into new retail or living space. You need only look at the soon-to-open Kudzu Seafood on Poplar, Famous Mike’s nearby, the Macon Beer Co.’s new taproom, which is nearing completion, or the dozens of other sites breathing new life, thanks to the preservation mind-set.

When he could, Sparks took walks down alleyways and even paid a visit to the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park while he was here.

“There are parts of history that just flash out,” he said of downtown’s buildings. “For me, it brings character to the city.”

In time, one stretch in the 600 block of Poplar that was used for filming will be torn down to make way for the planned Hyatt Place, a six-floor hotel with more than 100 rooms.

Joe Couch, another member of the “Hillbilly Elegy” crew, saw a good bit of that work during his years as a Savannah resident. But he knows you’ve got to pick your spots carefully.

Couch, a prop maker for more than 40 years, said he marvelled at what he saw downtown.

“These are beautiful,” he said, looking around. “You don’t see this much any more. A lot of places, they’re tearing down everything. You haven’t done that.”

Then he paused.

“You should show a reverence for them,” he said of the old buildings. “If not, they’re long gone.”