For Wini McQueen, it’s all about the story.

And she’s got plenty of them to tell.

Forging a working life as a fabric artist — “I really call myself a fine artist” — seems meant to be. But she does far, far more than just sew fabric squares together. In all her work, she’s stitching together stories on African-American history and culture, exploring issues of class, gender and society through her own seasoned views of life.

“I consider Wini McQueen to be Macon's greatest living visual artist,” said Carey Pickard, who has known and worked with McQueen for decades. “She is a genius who communicates important and often forgotten stories through her art.

“Wini's work encourages us to look at the world in new and different ways, and for that I am very grateful.”

When McQueen was a child growing up in Durham, N.C., in the 1940s, her grandfather would bring home scraps of cloth from the cotton mill where he worked. In time the 6-year-old took the swatches and fashioned her own quilt, her first fabric project. (She still has fragments of it.)

She started painting too — on paper, cloth, rocks, “whatever I could without getting into trouble.” She used a Paint-by-Number kit to create a colorful scene of dancers on a tablecloth.

“That’s how I know work and how I know life,” she says in a 2020 Museum of Arts and Sciences video chronicling her retrospective exhibit there. “I piece it together.”

When Historic Macon sought to honor the history of its new office at the old Fire Station No. 4, we turned to McQueen to find a proper way — and she did. “The Recommission,” three strands of brightly painted old fire hoses, now hangs from the station’s former hose room.

“I’m always telling a story,” the 79-year-old said. “When I made ‘The Recommission,’ I’m telling a story about where this foundation came from and encouraging people to renew their thinking and their actions and look at the past and be considerate of what is right there at hand.”

Her exhibits — and teaching — have taken her around the world, from the Museum of Folk Art in New York and a quilt festival in Tokyo to the dusty roads of African villages.

But it nearly didn’t happen.

As she grew up, “Like many children, I just forgot art, left it behind,” she said. At Howard University, she majored in English. But she “happened into” courses on painting, drawing, art crafts and art history — “enough to know what art was about.”

And that’s where she discovered textile design.

With graduation on the horizon, “I realized that what I had studied was not what my life was going to be about.” One professor in particular — “and everybody in the art department — said you have to go further with what you’re doing.” They saw her natural talent, as did her boyfriend at the time, Marvin Holloway (remember that name).

“I had every intention of becoming something fancy, a fabric designer,” she said. She had a chance to go work in New York, “but I discovered that I really wanted to dye fabric, sort of as an art form or dye fabric for unique types of clothing. So I ended up teaching myself right out of college some of the techniques” for hand-stamping, painting and printing fabrics.

“And from there I began printing and dyeing cloth. And looking for a market — which I have never found!”

She moved back to Durham and started “a little fabric business.” She dyed cloth and even wholesaled a few orders to New York. She remembers living in an apartment one time and dyeing cloth out of her car, avoiding the landlady whenever she could.

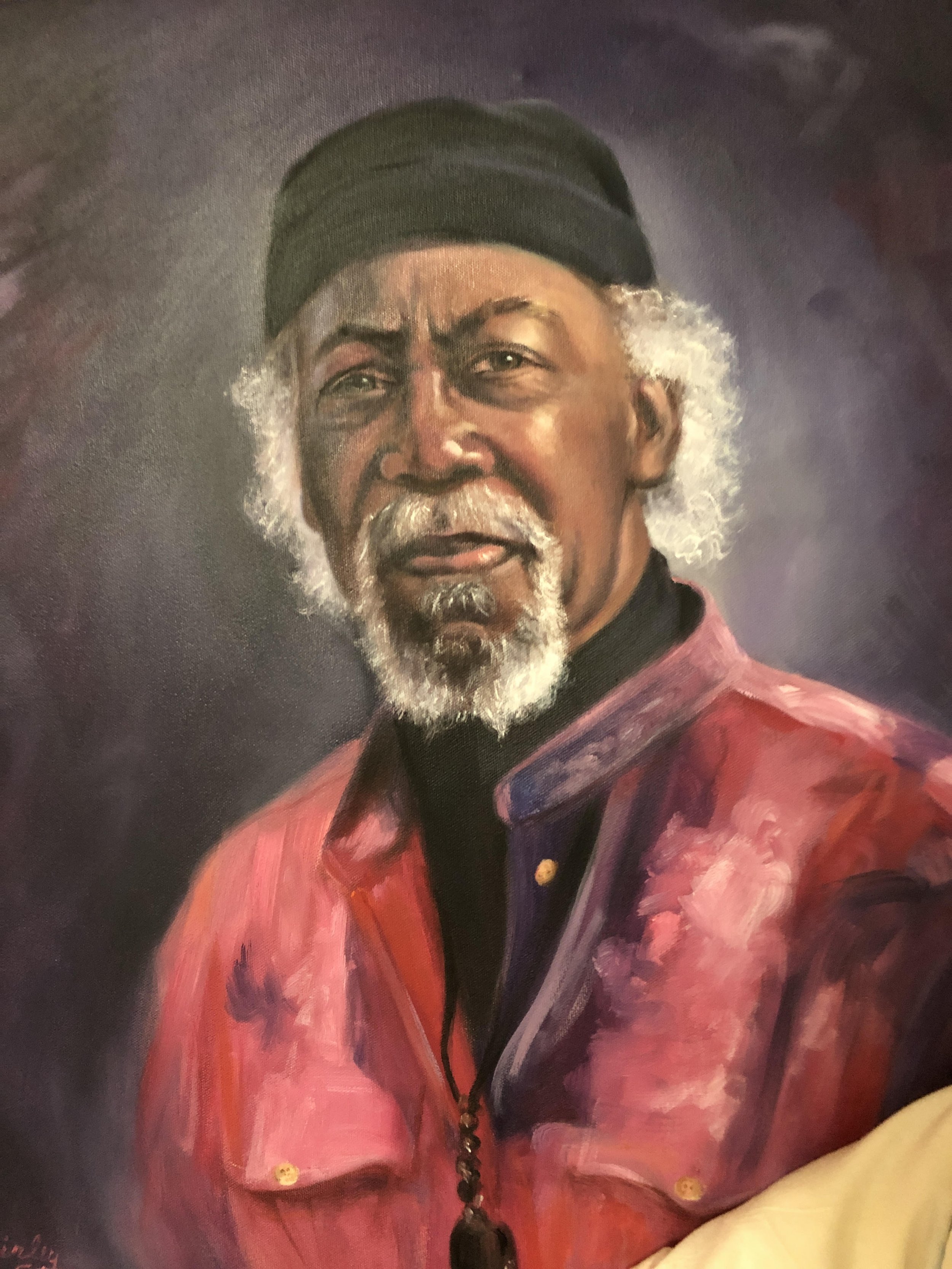

Milton Dimmons

“I was very serious about it, but that wasn’t a real market. But I couldn’t afford to keep producing. I didn’t have the space. I was a novice artist, a novice business person and living in the South, without advice. So everything was first-hand. Try this, try that, try the other. And it hasn’t changed!”

In 1976, she moved to Macon with her husband, Milton Dimmons, who had relatives here. He was her “work partner.” He had a law degree, but he couldn’t get a job in the legal field. So he helped McQueen with the technical parts of her work. He made her tools. He taught himself to sew. He was a reader and a learner. “There was nothing magic about it. It was hard work. But he made a way,” she said. Dimmons died in 2010.

Over the next few decades, McQueen found her footing as an artist. “I was alone. I had to rethink everything.” She also made everything from hand-dyed socks and scarves to notecards.

She had her own one-woman show at the Museum of Arts & Sciences in 1988, and as word of her talent spread, she earned grants and fellowships to travel and teach. Everywhere she went, she made a point to talk to black quilters and black artists in each community, seeing what they did and how they did it.

After that first MAS exhibit, she made a large quilt called “Family Tree” — a story quilt — that’s part of the museum’s permanent collection.

“I thought, ‘I could give a little of my time to making story quilts if I thought they would be models for learning about history.’ So I began exploring quilts that taught lessons about issues related to black people.”

A tiny cotton boll.

During her trips to Africa, “I became very conscious of how important cotton was in their lives. I saw spinners and weavers and fabric artists, people who tie-dyed. At some point I came back to stories about slavery. What was the most impressive body of stories I saw were about the African person and the experience in the cotton fields. And I wanted to not only read everything I could about it but to make art about it.”

“I realized that all my life, that was what had been the moving spirit. It was my source.”

About three years ago, her life took another unexpected twist. Her college boyfriend — yes, Marvin Holloway — reached out to her on Facebook. He was living in Miami, but he often visited his mother, who lived in Albany. He wanted to pay McQueen a visit in Macon, talk about the old stories and people they had known 50 years ago and see some of her work.

Holloway and McQueen at the HMF office.

“I hadn't seen Marvin or heard from him, didn’t know anything about what had happened to him,” McQueen said. “He was the first person who encouraged my art” back at Howard. “I thought he liked me, but I think he just liked my art.”

Soon, it was like old times.

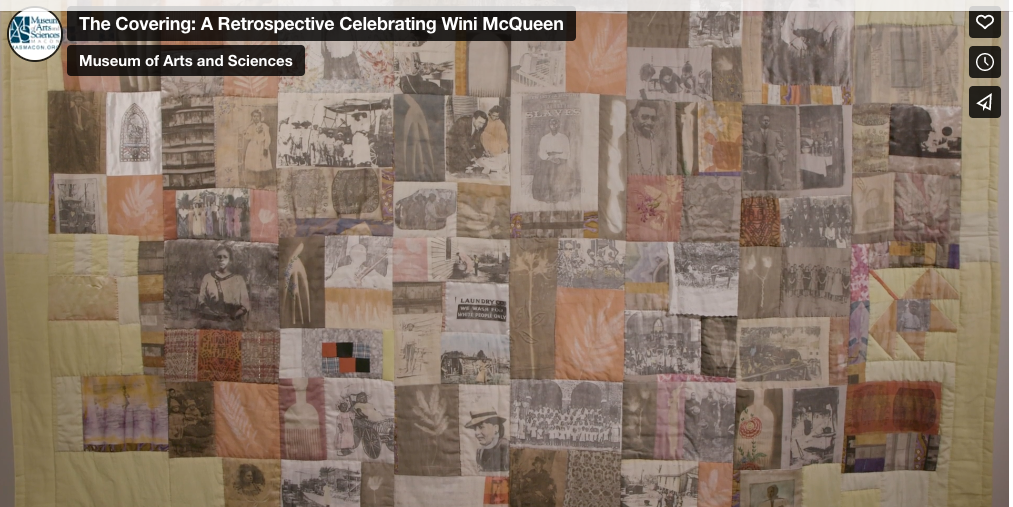

By 2020, they were working together on the three-gallery exhibit that became McQueen’s 50-year retrospective, called “The Covering,” (https://bit.ly/3VIilT8) at the Museum of Arts and Sciences. It featured examples of her work from previous periods along with new paintings, handmade and hand-dyed clothing, and a room-size conceptual work. (Susan Welsh, the museum’s executive director, called it “a monumental creative statement.”)

“I concentrated on my experience as an artist as it related to cotton,” she said, drawing heavily from her trips to Africa. “So all of the pieces in the exhibit were from cotton. … I think about the world when I create. I think about the need for people to collect their memories and their histories.

“For me this was my contribution to culture, to history, to get that old sad story and make it brighter and bring it into a new century.”

The commissions are still rolling in too. A recent one involves the Mount Willing Quilters near Fort Deposit, Ala.

“They commissioned me to make a quilt that included the names of 150 people who had been enslaved but whose names had been forgotten or whose names were on the verge of being forgotten,” she said. It’s called “Somebody’s Calling My Name,” taken from the title of the old Negro spiritual.

“What you see in history is that black people had no names that were respected. We came here with African names. No one bothered to recognize those. If you remember (the book and TV miniseries) “Roots,” there was Kunta Kinte, who refused to give up his African name. … They sent (me) these 150 swatches. What I did, besides piecing them together to make a quilt, I also told a story through documents about how the names were lost.”

“If I can make art objects that will help to explain or express black people in history, in our struggles, I want to do that.”

In Macon, she’s been working for almost two years on an artist-initiated project called “The Canopy.” Holloway helped her with it, and he has been an invaluable collaborator on other projects too.

“If you can imagine about 150 wall hangings, wall panels, that hang directly from the ceiling. Many of them are shaped. They’re shaped like cylinders. They will just hang down.”

It will be in place inside Macon Mall for most of 2023 as part of the city’s bicentennial celebration.

These days, McQueen sees the arc of her art — her life — in novel ways, like new colors reflecting from bright glass. She’s integrating quilting, photography, painting and the talking-story tradition into the modern, contemporary art canon.

“I have begun thinking about new ways of expressing old traditions and old issues and the past, but I’m working toward an understanding for the now — and for the future,” she said. “I don’t think I make quilts anymore. I’ve evolved. I think I’m taking quilting elements through a new passage and into an abstract form that is enlightening and encouraging.”

It’s a kind of artistic cotton ginning, as it were, drawing even more uses from the cotton boll as she shares herself with the place she calls home.

“I came from a community where people worked in cotton,” she said. “I have lived — surviving — working with my hands all my life, just as my family did.

“We had hands, and that’s how we survived.”