She couldn’t believe what she was seeing.

But the words were right there in front of her, even if they were hard to read. There was no mistaking it.

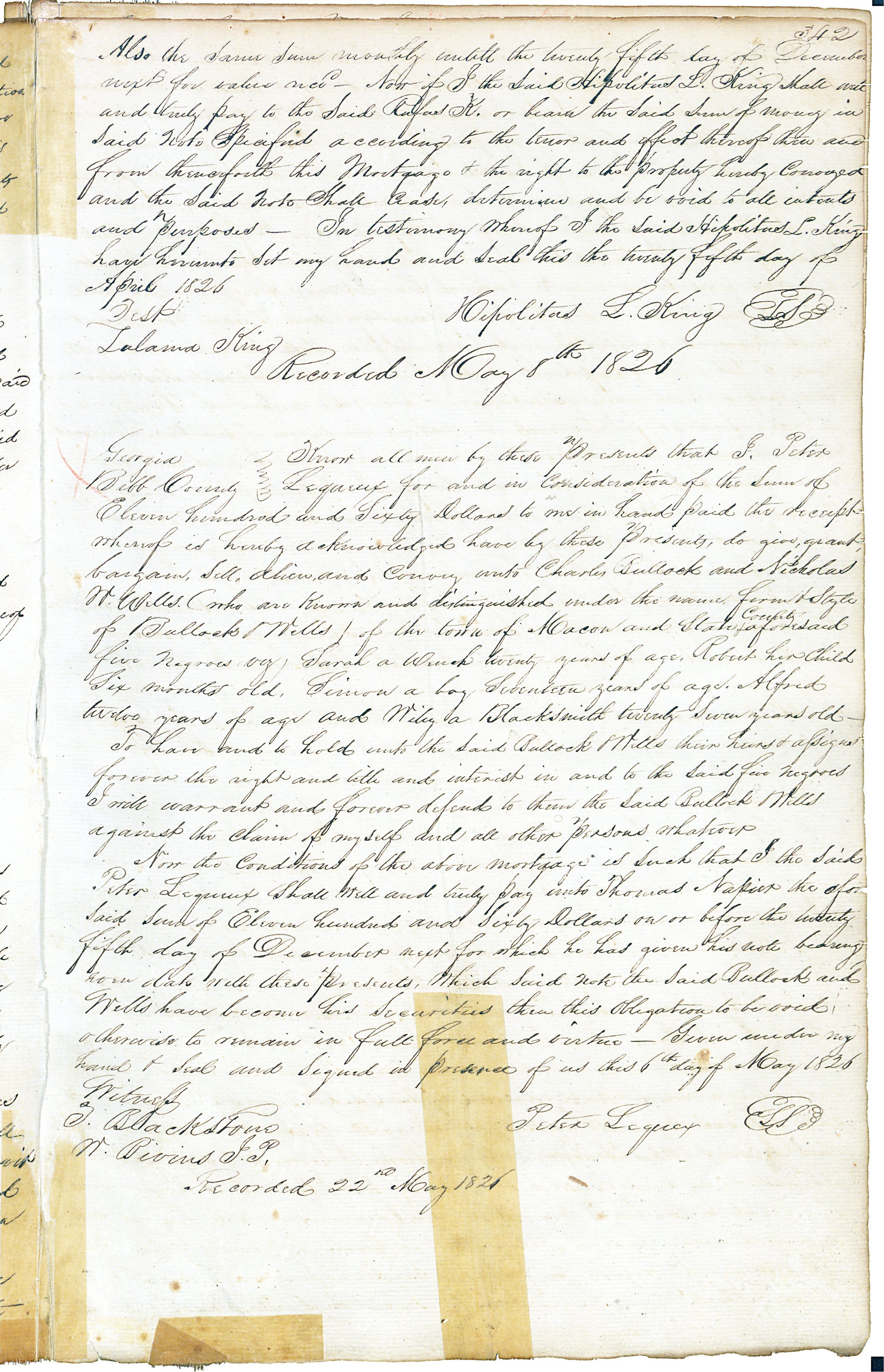

“In consideration of the sum of eleven hundred and sixty dollars, … do grant, … sell and convey … five Negroes (:) Sarah, … twenty years of age; Robert her child, six months old; Simon, a boy seventeen years of age; Alfred, twelve years of age; and Wiley, a Blacksmith twenty seven years old.”

“It blew my mind,” said Erica L. Woodford, the clerk of Bibb County Superior Court. “All of the air escaped me. I got goosebumps.”

She ran downstairs to tell Stephanie Woods Miller, her chief deputy, what she had found. “Come here! You’ve got to see this!”

Erica L. Woodford; Stephanie Woods Miller.

They climbed the steps to an old mezzanine floor inside the office where ancient record books are stored. There, they looked at the deed books in astonishment. In page after page — 17 different volumes, it turned out — were entries of slave transactions in Bibb County from 1823 (the year Macon was incorporated) to 1865.

The names of enslaved people — reduced to chattel in more than 1,000 transaction records — were right there alongside entries for plats of land, houses or a horse and buggy.

The records showed that slaves were used as collateral for loans. The railroad leased them for work it needed. The city of Macon used them in its development — from road building and Ocmulgee River dredging to plantation life near the Ocmulgee Indian mounds.

And in 1835, Macon City Council members (known then as the Board of Aldermen) approved the purchase of eight slaves for the city’s first elected mayor, Robert Augustus Beall, for $10,000.

“Doesn’t that blow your mind? asked Dr. Chester Fontenot Jr., the director of Africana studies at Mercer University. “You have the city government saying: ‘Go buy you a slave.’ This is tax dollars, paid for with city funds.”

Now, research of the records — more than five years in the making, in part because of the pandemic — has coalesced into the Enslaved People Project, which just won a 2023 Preservation Award from Historic Macon. The slave records are being digitized, and in time they will be searchable by name, transaction amount, characteristics and more. It’s been a painstaking process, requiring at least three sets of eyes on each document to ensure accuracy, then cataloging details in a spreadsheet.

“It’s important to shed light on their stories individually and collectively to humanize these people who were forced to work under certain conditions so that we can have a thriving city,” Woodford said. “Those Black people built the wealth of the landowners. They built the roads that we drive on, the buildings that we inhabit. They built this city.”

Macon residents with prominent names — names you see on streets and buildings around town — owned slaves too.

Finding the deed books was just blind luck. They’d been sitting at the courthouse for 190 years. After Woodford was elected in 2012, she took time when she could to familiarize herself with all the records in the office. One day she just happened to find old cabinets, pull-out file drawers — and the deed books.

“It was amazing — and astonishing,” she said. “(I thought) Here is actual proof of a taboo topic that we rarely speak on, the subject that now is a no-no to talk about in schools and educational settings.”

Some of the slave records list names. Many do not. The transactions range from young children to people in their 70s. Some of the entries list family relationships. Most do not. And sometimes dozens of men and women were sold at one time. (One deed record noted 220 people sold in one sale.)

Woodford talks often about one of the first entries she ever saw, in deed book 3, page 6. It listed the sale of “a certain Negro girl by name of Harriett, aged eleven years, very light complexion, … straight hair, warranted to be sound and well,” for $225 to Alexander Bryan of Bibb County on Aug. 8, 1828. Bryan, the next entry indicates, then sold Harriett — “together with the future issue and increase of said female slave” (i.e., her children) — to James Taylor, a Savannah merchant, for $275 on June 17, 1829.

“What’s interesting,” Woodford said, “is that none of the other transactions selling humans described them in such detail. “Maybe she was beautiful. Maybe she was lovely to look at.”

Often, Miller said, when they have those descriptions, they’re selling them for their physical attributes,” sometimes for sexual purposes.

Dr. Chester Fontenot Jr. (Photo by Bekah Howard, Mercer University)

“We have human beings who were bought and sold like chickens and cows for the purpose of profit — money — without any regard for their humanity,” said Fontenot, who coordinated research of the records. “Because those who were doing it just believed that Black people weren’t human. Or if they were, they were on a lower level of humanity.”

What’s clear from the records is that the families of enslaved people were often ripped apart. In one record, a mother and her children were used as collateral on loans to different creditors, and in time there was a default when someone failed to make the required payments.

“I realized that this mother and her children were likely to be separated because there were three creditors and three enslaved people,” Woodford said. “(I thought) I bet this story ends with her being separated from her children — and that they were young and would never know her” — because somebody defaulted on a loan.

And the sad truth is that the deed books don’t capture the full picture of slavery in Bibb County during those years. “If you come from somewhere else or you’re gifted certain property, it’s not necessarily recorded,” Woodford said. “You already own the property.”

(Macon, as history shows, was a major slave auction site in the 19th century, as noted in a 2020 New York Times article. Among the prime locations: Cotton Avenue, near the former site of the Confederate monument before it was moved, Pine at Fifth streets, and near what is now the Macon-Bibb County Government Center.)

“It takes the theoretical and makes it very real,” Miller said of the deed records. “It’s one thing to read about it in a history book where it’s a five-second moment of Black history, and it’s another thing to be looking at something that someone transcribed by hand.”

The records are written in a script font — similar to cursive — that “is like learning another language” when you’re trying to decipher it, Miller said. It’s hard on the eyes.

Volunteers and Mercer University students and employees, under Fontenot’s watchful eye, went through the documents page by page, making sure they didn’t miss an entry. Others checked their findings to ensure the accuracy, as did Julie Grimm, the office’s historical preservation clerk.

About 300 records are viewable now, but after they’re scanned, all of the records will be searchable from a link on the clerk’s office website (https://bit.ly/3P9scAA). The goal? By the end of 2023, you’ll be able to enter a search term and go directly to the corresponding page.

“We want this to be as user friendly as possible while maintaining the integrity of scholarly work,” said Fontenot, who’s also working on a narrative component for the project to add context.

Uses of the records are unlimited, Miller said. “We could offer sessions for genealogists on how to search, to students, writers, podcasts, TV shows (such as) ‘Who Do You Think You Are.’ ”

For those who have worked on the records for years, Woodford acknowledged the toll it has taken.

“There is definite psychological trauma,” she said. “You look at the trauma of what happened during slavery, and then you’re reliving that every single day (during the research.) And then you’re watching the news. And then you’re trying to figure out if there is a nexus between the dehumanization of Black people in 1823 versus current trends, current happenings in society. … It’s taxing.”

The work brought tears to Grimm’s eyes at times. “You can’t believe how people treated each other,” she said.

“There were times I got overwhelmed,” said Fontenot, who went through two of the deed books himself. “I had to take a break, … go outside, walk around. We were all like that. It was intense.”

The work, he added, “has meant to me something almost sacred. Unlike any other group of people here in this country, we are the ones whose history and culture and ties to the past were intentionally severed — an attempt made to try to remake us in the image of those who bought us and owned us.”

As word has spread about the project and as it winds toward conclusion, the women say they’ve gotten requests for more information from across the country. They say they’ve gotten no pushback about the project.

“At least not to my face,” Woodford said.

Elsewhere in Georgia, such records have been lost to courthouse fires or floods. And some have been discarded or destroyed.

“In one county in the metro area, some of the historic books were found in a trash bin — and in south Georgia as well,” Woodford said. “The genealogical society saved the records because they had been thrown away. So we’re lucky. We’re blessed.”

Fontenot likens the records — what they mean and the context surrounding them — to debates about “blood diamonds,” or diamonds sold to fund violent insurrection in the regions where they are mined. His chief aim has been to strip away the “false narrative” about slavery: that things weren’t so bad, that everyone worked together, got along and cooperated.

“If you could take out the pain, if you could take out the injustice, if you could take out the horror, … the separation of families, the rape of the women, if you could just strip out all of this and just look at these documents in terms of historical material, you would get excited,” he said. “But you can’t do that.

“I can’t talk about this project without getting all riled up,” said Fontenot, who’ll retire next spring after 49 years of teaching. “But I’m pleased to be able to get riled up with this project and all that it implies and encompasses for people. This is my way of leaving something for the community, especially people of African descent.”

Woodford and Miller see the records as a “catalyst for conversation,” not as a source of guilt or to cast blame.

“I’ve been (in settings) where people say, ‘Why do we have to talk about that? Well, in some corner, somebody’s already talking about it. Some of these stories are passed down at Thanksgiving on both sides of the fence. Some of this is not quite as hidden as people would like to think.”

She added, “I think it’s not about pointing fingers to make anyone feel bad about the history. We are only responsible for our own actions. We can’t be responsible for our parents or grandparents or our great-great-grandparents’ actions. We are just shedding light on the truth of what happened so we can learn about history — we can learn about our shared history — and hopefully we can grow from it and be better humans.”

It all comes down to one thing for Fontenot: “Let’s tell the truth about what happened.

“Once we do that and get a fuller understanding of what happened, that gives us a baseline to start figuring out why we’re in the state we’re in now. Only by recognizing that there’s a wound can we cure it and heal it.”

In the coming weeks, the Tubman Museum plans an exhibit on the Enslaved People Project. Inside the museum will be an original deed book, as well as 25 or so duplicate pages so that visitors can see for themselves what the records said — and looked like.

For Macon, the records can be another step in community understanding and reconciliation. At least that’s Woodford and Miller’s hope.

“When you start talking, you never know what blooms from beginning the conversation,” Miller said.

“Sometimes you need some ripening, a little distance from that history, to be able to say this is important and this is how you can talk about it in a way that doesn’t set the world on fire,” Woodford said. “Because truth has a way of rising anyway. You can only suppress it so long. It’s better to get ahead of it and be part of what’s next. We don’t want to be stuck in 1860.

“We want to look forward to a different kind of future, and I think we want to do that future together,” she said. “That’s the only way Macon survives.”