Eustace Edward Green is back in the news.

And that’s saying something, since he died more than 90 years ago.

E.E. Green

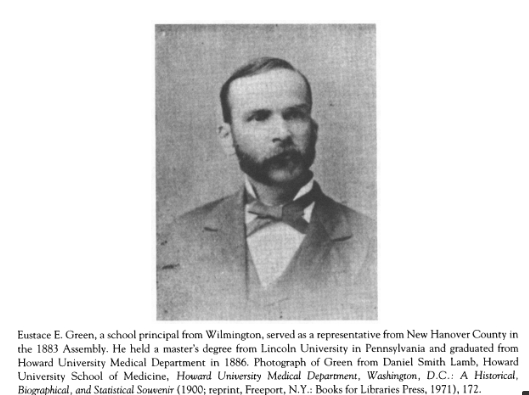

Green — better known as E.E. Green — was a slave when he was born in 1845. He had no access to formal education. But by the time he died in 1931, he had become a doctor — maybe the first licensed Black doctor in Macon, owned a pharmacy and taught at two universities.

The more you learn about him, the more you wonder how he made time for all that he accomplished.

His life — and now attention to his home on Madison Street in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood — have whisked him back into the public eye. Earlier this year, the play “Healing a Haunted House” at the Grand Opera House told his story, and now his former home has made Historic Macon’s 2022 Fading Five list, after a nomination by attorney Nathan Corbitt.

Green became a free man when the Union army rode into his hometown, Wilmington, N.C., on Feb. 25, 1865. From that moment on, it was as if someone had lit a fuse in him, unleashing years of pent-up yearning for learning. That passion for education — for both himself and other Black men and women — was a driving force in his life.

He found work as a carpenter by day and attended night school for two years. In that short period of time he readied himself for college at Lincoln University, from which he graduated in 1872 and also obtained a master’s degree.

Over the next 10 years, he taught school, worked as a court clerk and was a school principal. Then, at age 37, he served a term in the North Carolina House of Representatives, where he quickly became the leader of the African-American bloc, according to an article in the North Carolina Historical Review called “The Class of ’83: Black Watershed in the North Carolina General Assembly.”

“His deferential manner and quiet dignity helped him engineer strategic compromises, perhaps even allowing him to deal on nearly equal terms with white politicians in both parties,” according to the article. In fact, he was the first Black House member to be nominated for speaker of the House (He received two votes.)

Afterward, Green decided to become a doctor and attended Howard University Medical School, graduating in 1886. Then he, his wife and their children moved to Macon. They built their home in Pleasant Hill in 1890 at what was then 405 Madison St., near Macon’s main post office. Green also opened a pharmacy, and he was a landowner who became a landlord in the neighborhood.

Julia Rubens

“He did so much in his life and he chose Macon to settle his family in — and really became a backbone of the early Pleasant Hill community,” said Julia Rubens, who co-wrote “Healing a Haunted House” along with Dsto Moore and Nancy Cleveland. “It’s such a fascinating story and can provide many other generations a lot of hope, a lot of sense of Black excellence and a lot of inspiration.”

Green was not one to draw attention to himself, though. He was an advocate for education and encouraged other Black men and women to improve their lives through schooling. He took considerable time to share his knowledge and mentor people he knew, including a man named Henry Rutherford Butler, tutoring him in the evenings after work so Butler could go to college. (Butler, an Atlanta resident, would later become the first African-American to receive a pharmacy license in Georgia.)

This old marker near Green’s home gives another indication of his importance during his life.

Green himself started a drug store on Cotton Avenue in the 1890s called Central City Drug Store. Within a few years, he moved it to his home. No one is sure why, but a leading theory is that the rise of open intimidation and violence — including lynchings — against Black residents in the decades after Reconstruction played a role. And at times he may have treated patients in his home too.

You won’t find Green quoted often, and it’s not easy to build a comprehensive profile. After he became a doctor, leading Black periodicals of the day came to Macon, visited with him and wrote up his story. He is quoted in one, “The History of the American Negro and His Institutions,” on what he considered to be the road map for success for Black men and women: “Good character, square dealing with all people, strict attention to business, Christian education, and a goodly portion of this world’s goods honestly acquired.”

The article continued: “The Bible he places as paramount, and its influence has been largely manifest in his career. He is also fond of American history and choice English literature. He has also traveled extensively in the South, West and Northwest.”

Green and his wife, Georgia, had four children. Two of his sons went on to work in medicine. His daughter was a college graduate — a rarity at the time — and married a doctor.

He was active in Washington Avenue Presbyterian Church (he and his wife joined on Jan. 8, 1888), and he represented his presbytery in three General Assemblies. He was also chosen moderator of the Atlanta Synod at Macon in 1910.

There aren’t copies of lectures or speeches he gave after he founded (and served as president of) the Colored Medical Association, an organization for Black medical professionals in the state. He also served as president of the National Medical Association, a countrywide group for African-Americans in medicine.

But Green’s story is as much about the Pleasant Hill community as anything else. And there’s no better authority on that than Dr. Tom Duval, a tireless advocate for the neighborhood and teaching its rich history to today’s students.

Dr. Tom Duval, outside Green’s home on Madison Street.

“Pleasant Hill was the place to be because these were people that were moving up,” he said. “They had a purpose in life. They knew who they were, and they were surrounding themselves with comparable people.”

“We had every social stratification living in this small area,” he said. “We had a microcosm of the world. Even though you may not have been blessed to be in a middle-income family, you were in close proximity to see other prosperous African-American people. So you had these mentors, these people that you could identify with, just a few blocks from where you’re living.

“Per square foot,” he said, “this place has probably produced more successful African-Americans than any place in the United States. Why is that? I think it is the combination of the history of the American Missionary Association,” a leading abolitionist group, “and also the griots that told our story and shared the story in schools and churches. Eventually we got a library where our story was preserved.”

Rubens shares his sentiments about Pleasant Hill — and Green’s stature and influence during his lifetime.

“What stands out to me is an incredible life of determination and Black excellence,” she said. “He really represents the character of Pleasant Hill, which had all of these professionals who were just incredible strivers in their field. This was a man who only served one year in the statehouse and yet got nominated to be speaker of the House. This is a man who decided to complete medical school in his 40s. … This is someone for whom determination and belief in education was just vitally important.”

Green died in Detroit on June 1, 1931, while he was visiting family there. He is buried in Macon’s Linwood Cemetery.

Now, 91 years after Green’s death, Duval is glad he is getting the recognition that he deserves.

“He could have come down here and been the big fish in the pond and just spent all his money on ostentatious stuff — great big house, great big car, fancy clothes,” Duval said. “But what did he do? He came down here and spent his time training the first pharmacists in this area, giving something back. And he did that with his personal time and money.

“To me, that’s a man of honor.”